Scraping the Sugarcoat

Abstract:

Web-scraped data are used to put a Rubik’s cube competition result into perspective. The sugarcoating consists of altering the sampling frame of the comparison to the more relevant population of senior first time cubers.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The

markdown+Rknitr source code of this blog is available under a GNU General Public

License (GPL v3) license from github.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The

markdown+Rknitr source code of this blog is available under a GNU General Public

License (GPL v3) license from github.

Motivation

I just finished teaching an undergraduate course on data wrangling with R at Stockholm University about the tidyverse, SQL, and web-scraping1. Inspired by Jenny Bryan’s STAT545 course the course used GitHub as communication platform. Similar to the userR! lightning talks, each student had to pitch their project work in a 5 minute presentation in order to woo other students to read their report. I was utterly amazed by the content of the reports and the creativity of the presentations, which included sung slide titles, shiny apps, cliffhangers, and much more. Enabling mathematics students to pull their own data gives them a power to realize ideas and test hypothesis that were not possible before! Most of the students did web-scraping or API calls to get their data. Since I - thanks to support by two TAs - never got around to implement any scraping myself, a blog post feels like the right way to catch up on this.

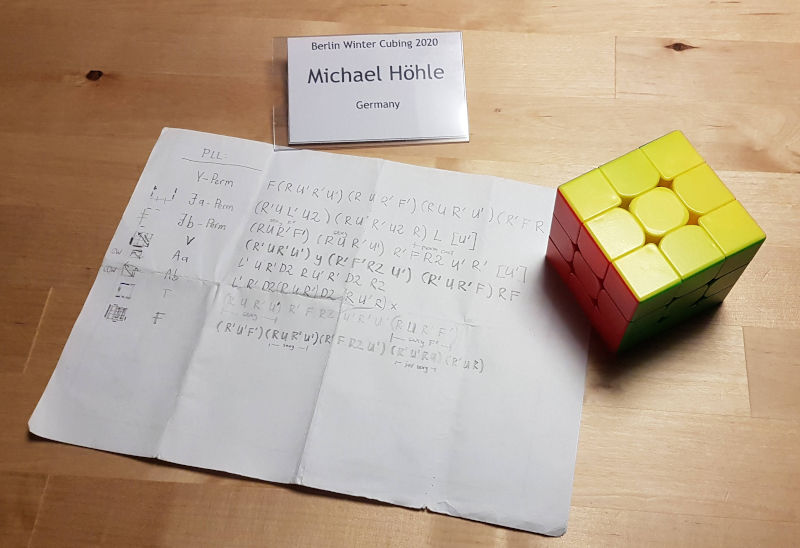

After finishing last place in the Berlin Winter Cubing 2020 competition, there was an acute need to sugarcoat the result. The aim of the post is thus to substantiate that this last place was purely due to lack of competitors. 😃 Since at the time of the analysis, my results were not yet part of the World Cube Association (WCA) results database, the idea was to use web-scraping from the live feed to pull my results and compare them to the database. The resulting R code is available from github and is described below.

Scraping WCA live results

WCA competition results are reported live, i.e. as they are entered, by a dynamically generated web page. Below is shown the round 1 results of the Berlin Winter Cubing2020 competition. In case of the traditional Rubik’s cube (aka. 3x3x3) event, one round of the competition consists of 5 solves. A trimmed mean is computed from the five solve times (aka. Ao5) by removing the best and worst result and averaging the three remaining results.

The data science job is now to automatically scrape the above results

as they become available. In other words dynamically generated pages are

to be scraped. The post RSelenium

Tutorial: A Tutorial to Basic Web Scraping With RSelenium provided

help here, including an explanation on how to change the web

driver version to match the installed Chrome version. The Rselenium

based scraping code to get the above table looks as follows.

library(RSelenium)

driver <- rsDriver(browser = c("chrome"), chromever = "79.0.3945.36", port = 4568L)

remote_driver <- driver[["client"]]

# Fetch WCA live results of the 3x3x3 round 1 from the Berlin Winter Cubing 2020 competition

url <- "https://live.worldcubeassociation.org/competitions/BerlinWinterCubing2020/rounds/333-r1"

remote_driver$navigate(url)

# Wait a little to make sure page has been generated.

Sys.sleep(5)The selectorgadget

bookmarklet was then used to find the css selector of the table

containing the results and the rvest::html_table function

was used to extract the table as a data.frame.

library(rvest)

# Extract table with all results from round 1

results <- remote_driver$getPageSource() %>% .[[1]] %>% read_html() %>%

html_nodes(css = ".MuiTable-root") %>% html_table(header=1) %>% .[[1]] %>% as_tibble()

# Small helper function to parse WCA results with lubridate, i.e. add "0:" if no minutes.

time_2_ms <- function(x) { if_else(str_detect(x, ":"), x, str_c("0:", x)) %>% lubridate::ms() }

# Convert reported timings to lubridate periods

my_results <- results %>% filter(Name == "Michael Höhle") %>%

mutate_at(vars(`1`,`2`,`3`,`4`,`5`,`Average`,`Best`), .funs= ~ time_2_ms(.))In other words, my first (and as of today only) official 3x3x3 average is 1M 18.05S which corresponds to 7805 centiseconds. This is much better than the 3 minutes anticipated in my analysis from May 2019 and was well under the 4:00 time limit of the round. Still, I finished last place in the 3x3x3 competition (rank 84/84). However, the competition was in no way representative of my peer group (senior newbie cubers) as, for example, number 1, 3 and 7 of the World Championship 2019 also competed.

The aim of this post is thus to use a data based approach to alter the sampling frame of the comparison in order to make the comparison more relevant (aka. sugarcoating):

- How does my result rank within the population of German first time competitors?

- How does my result rank within the population of age 40+ cubers?

German first time competitors

The WCA results database is used to determine all 3x3x3 results by German cubers a shown in the previous Speedmining the Cubing Community with dbplyr post. We perform a comparison with the round 1 results of all German first time 3x3x3 competitors within the last 5 years.

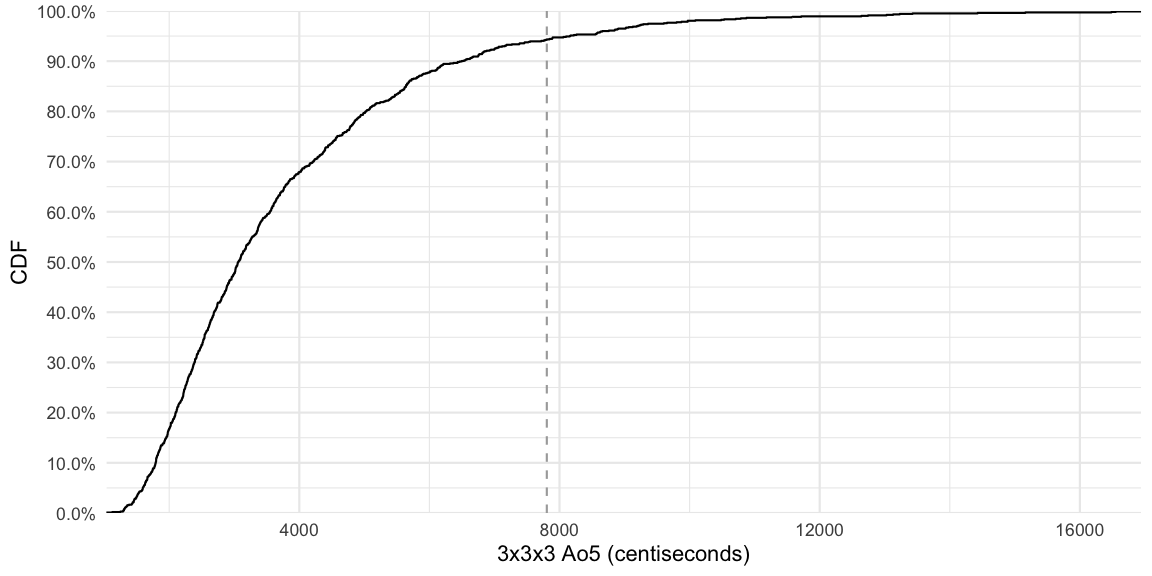

This gives us 1024 cubers to compare with and constitutes a more relevant population of comparison than, e.g., podium contestants from World’s 2019. The plot below shows the cumulative distribution of the Ao5 the cubers got in round 1 of their first competition. Given a value on the x-axis, the y-axis denotes the proportion of cubers which obtained an average lower or equal to the selected value.

From the graph it becomes clear that my time corresponds to the 94.34 percentile of the distribution, i.e. 94% of the 5 last years German first time competitors had an average better than me in their first competition. This means that the performance was just about within 95% percentile of German competition newbies. Yay!

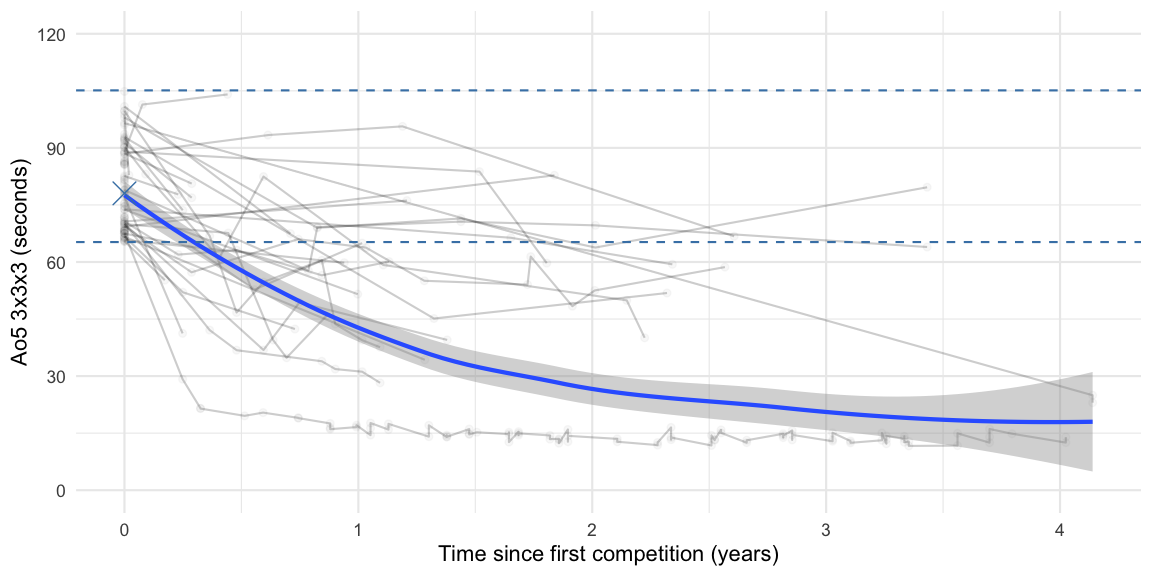

How do these cubers evolve after their first competition? I was particularly interested in the trajectory of cubers within my skill bracket, which here shall be defined as an average located between my best and worst solve time of the round, i.e. 65.24s and 105.12s.

In the figure, the two horizontal lines indicate the limits of the skill bracket and the cross denotes my average. A smooth line is fitted to the longitudinal data, due to simplicity the smoothed fit does not take the longitudinal data structure and the drop-out mechanisms into account. By focusing on the cohort of cubers starting to compete within the last 5 years induces censoring: Cubers who started with competitions for example 1 years ago, will not be able to have results more than 1 years back in time. Still, a clear downward trend is visible, if the cuber goes to further cubing competitions. However, only 25% of the first time cubers have a second competition recorded in the data. Somewhat demotivating is to see that only 3 out of the 84 first time cubers in the skill bracket manage to obtain a sub-30s average at a later stage.

Comparing with senior cubers

Michael

George maintains an unofficial ranking for the

senior cubing community based on the WCA results database and a

voluntary registration of senior cubers. As in other sports disciplines,

“senior” is defined as aged 40+. Based on a one-time anonymised extract

from the WCA database containing the true age of the cuber, the

completeness of the self-report sample as well as a statistical

extrapolation of the true rank within the WCA 40+ population can be

computed: Around 30% of the senior cubers are contained in the

self-reported sample. The WCA id as well a personal records of all

self-reported “old-cubers” is available in JSON format’ish format and

can be scraped using the httr

package.

response <- httr::GET("https://logiqx.github.io/wca-ipy-www/data/Senior_Rankings.js") %>%

httr::content(as="text") %>%

str_replace("rankings =\n", "") %>%

jsonlite::fromJSON()From the response we can extract the WCA id of the self-reported senior cubers, which we then match to the WCA database to get their round 1 result at their first cubing competition. Note: This is a slight approximation to the population of relevance, because the cubers could have been younger than 40 at the time of their first WCA average. Furthermore, note also the cohort effects as cubing times in general have declined, e.g., due to better hardware.

# WCA IDs of the senior cubers

ids <- response$persons %>% pull(id) %>% unique()

# Extract all WCA 3x3x3 results of these senior cubers and restrict to their first

# competition result.

first_senior <- detailed_results %>% filter(personId %in% ids) %>%

group_by(personId) %>%

arrange(date,roundTypeId) %>%

filter(row_number() == 1) %>%

ungroup

# Percentile in the first comp average of senior cubers

senior_percentile__first_average <- ecdf(first_senior %>% pull(average))(my_avg_333)From this it becomes clear that my average is located at the 70% percentile of the first competition result of (self-reported) senior cubers. Not so bad at all. How do comparable senior cubers evolve over time? The graphic below shows how the senior 289 cubers, who participated in their first competition within the last 5 years, evolved over time.

About 81% of these senior cubers attended more than one competition, which is a higher proportion than in the overall cubing population, but is likely to be explained by the sampling bias of senior cubers having to self-report. Smoothed mean tendencies in 5 skill brackets, i.e. cohorts of [0,30), [30, 60), [60, 90) and [90, 120) seconds Ao5 in their first competition, are computed and visualized. The cross indicates my Ao5 result. Interpretation of these curves is again complicated by drop-out processes and cohort effects. Still the curves show that if I stick to cubing, I have a good chance at becoming sub-50, maybe even sub-40, within one year!

Discussion

It’s only logical and in the nature of competitions that somebody has to finish last. From my previous analysis I knew this would be a risk, but being both the age and skill outlier is still a bit of a party pooper. On the positive side: Signing up for a competition helped me shuffle some time free to practice, I learned how a competition works, saw no. 1,3 and 7 from the World’s 2019 final in action and got to judge other cubers. The statistical analyses in this post show that, by rectifying the sampling frame to a more comparable group, results are not so bad at all. 😃

Technical note

I cube with a stickerless YuXin Little Magic using CFOP (F2L+4LL accelerated with additional PLL algos). My 3x3x3 PBs at home are 46.19 (single) and 58.10 (Ao5) with scrambles generated by cstimer. This illustrates that a competition, in terms of pressure, is something else than cubing relaxed at home. In one of the attempts I failed the T-perm twice - despite having made a regular expression exercise for it as part of the course…

Acknowledgments

The terms of use of the WCA database requests any use of it to be equipped with the following text:

This information is based on competition results owned and maintained by the World Cube Association, published at https://worldcubeassociation.org/results as of Jan 22, 2020.

Besides this formal note, I thank the WCA Results Team for providing the WCA data for download in this comprehensive form! Also thanks to Michael George for maintaining a database of senior cubers.

Literature

Original course development was done by Martin Sköld in 2018-2019.↩︎